Jim Rauland, the writer of ‘Corporate Rock Sucks’ chats with Dom Tyer about how SST Records changed the direction of punk rock, post-punk, indie, and rock and roll.

Set up by Black Flag’s Greg Ginn to release his band’s first record, US punk label SST Records went on to rule the 1980s underground, releasing albums by Hüsker Dü, Minuteman, Bad Brains, Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr, Soundgarden and many, many more.

Telling the upstart label’s story in full for the first time, ‘Corporate Rock Sucks’ is a page-turning account of how SST took on the corporate machine with furious dedication and a combative stance that ultimately even extended to its own bands.

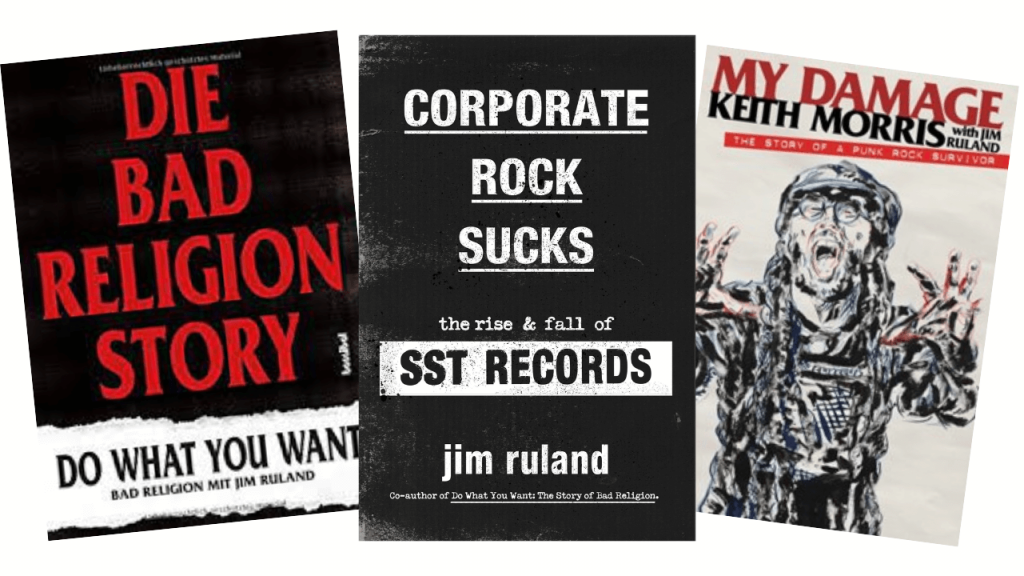

The book’s author is Jim Ruland, whose previous credits include Keith Morris’ memoir ‘My Damage’ and ‘Do What You Want: The Story of Bad Religion’. Punktuation connected to his San Diego writing room via Zoom for chat about all things SST.

Starting at the beginning, what was your entry point to the SST world?

I did not grow up as a huge fan of SST Records. I graduated from high school in 1986. So, by that time, Black Flag had broken up, and when I was really starting to get into punk, I was in the Navy and in college; then SST was on the decline.

Shortly before the year 2000, I moved to Manhattan Beach, which is the beach north of Hermosa Beach. And you know, being interested in punk, I just naturally gravitated towards Black Flag, Circle Jerks, Pennywise– bands that came from Hermosa Beach.

The Descendents – got to put them in there too. There are so many bands that came out of that area, and I just started to learn the lore and the mythology of those bands.

Fast forward to when I’m working with Keith on ‘My Damage’, we took some field trips to Hermosa Beach, and he showed me, ‘this is the school I went to’, ‘this building here used to be a little janitor’s closet where I would get high and sell speed to my classmates’ and stuff like that. And we walked right by the house where Black Flag had its first rehearsals. That made it more real for me, and I became much more interested in the label.

How did that interest translate into you working on its story?

I never really thought about doing a book about SST, because SST was Greg Ginn’s empire, and Keith has a lot of very choice words for Greg. So, the anger and the animosity was very much real. I’m Team Keith, and I’m loyal to Keith. So I never really thought that I was going to explore Greg Ginn’s side of the story and what he did with SST.

There was a small press that reached out to me about doing the book. I told Keith I thought it was a terrible idea. But then I talked to him, and he was like, ‘Nah, man, you should do this, you know, it’s all about the music’.

Things didn’t work out with that press, but they got it further enough along that we were able to take it to another [publisher] – the same one that I worked with on ‘Bad Religion’ and ‘My Damage’. And Keith gave me a list of numbers to start out with, and we’re off to the races.

The book came out earlier this year, and from what I’m hearing, it’s generating some mixed emotions in readers.

The book is a celebration of all the decades of music, the nearly 400 releases that came out from SST, some of it changing the shape of and direction of rock and roll and indie music and post-punk and punk rock too. It’s also the label that Black Flag built, but at the end you find out that [despite] all this amazing music, so many of the artists are upset with Greg Ginn, feel betrayed by Greg, by the whole experience.

So, I do get some bummed-out messages. But I also think people will like the structure. Each chapter is ‘SST versus…’ a record label or an era or something like that. And it’s a way to organise it in a way that’s more than just chronological. Because there’s this received wisdom that Greg Ginn and SST were going along gangbusters and then somewhere along the line lost the plot and turned on everybody. And there’s some truth in that.

If you really look at the story of SST, you see that Greg Ginn was immensely combative. Instead of shying away from battles, he went into the fray with all guns blazing, even when it was maybe in his best interest not to. A lot of people who had gone into the story with their minds made up about Greg came back saying, ‘Wow, I had no idea that the stakes were so high’, and come away with a bit more respect for what they did – not for the result, but for what SST achieved.

Looking at what the label achieved, SST had plenty of well-known bands on its roster but were there ones you felt deserved more attention?

Things like The Stains is where I maybe put my thumb on the scale a little bit, because here’s an LA punk band that’s pretty much been written out of LA punk history for no good reason other than they broke up before their first album came out. They weren’t the wealthy white kids, not that the LA story is full of those types of people, but I felt like The Stains were like a forgotten band, and that their SST debut (SST 13) is just incredible and one of the most dynamic records that they put out in the early years.

In pulling the story together and having an overview of the label in its entirety, what’s your take on why SST is so important?

Just the scope, the sheer number of records that they put out and the time that they did it, and how they linked the punk movement to Nirvana, basically. SST became the sound of the underground and the level of commitment and the level of hardship that every one of those bands endured.

If it had been another group of guys, I don’t think it would have had the same result – it wouldn’t have made it out of the ’80s. Most labels would have just folded up right when MCA pulled the plug on Black Flag’s ‘Damage’, I think most people would have been like, ‘Well, boys, we had a good run, but now the majors are crapping on our necks, and that’s it – let’s go to college’ or something, you know.

But Greg Ginn and [Black Flag bassist and SST co-owner] Chuck Dukowski and the rest of the label said, ‘No, we’re gonna fight it’. And I mean, those guys went to jail for SST. So I think that it’s pretty obvious what the label achieved is important, but no one else could have done it.

And what contribution did the work of Greg Ginn’s brother, the artist Raymond Pettibon, make?

It gave the label identity and, at times, a very disturbing one because of the genius of Raymond Pettibon. In the late ’70s, and early ’80s you have this growing sense of disenchantment from young people – the Moral Majority, the religious right is creeping up, and you have Reagan coming into power and the energy crisis in the late 70s, and young people were thinking, ‘I thought things were supposed to be better – it’s supposed to be like the 50s, right? Why are we fighting all these wars for this’.

Then you have this vision that Raymond Pettibone creates, a lot of which was inspired by the 60s and even before, like pulp fiction, the dark side of 60s counterculture – all kinds of naked hippies with knives and bad LSD trips. You combine that vision of America with what people were feeling in the 80s and it was very dark and very disturbing and it upset parents and it energised kids.

The story you tell is about the rise and fall of SST Records. At what point did the label’s decline begin?

The ‘jump the shark’ moment has to be the SNAFU with Negativland – the U2 seven inch where they got sued by everyone, and where Greg Ginn really showed his ass by suing Negativland. That was a big wake up call to a lot of people who are like, ‘Whoa, here’s this indie label and they’re suing their own musicians, like, what’s going on here?’

And yet, until that point, you can still see their finger on the pulse. They were even one of the many labels Kurt Cobain contacted when he was originally looking for a record label. Without the Negativland case, could SST have become a Sub Pop and continued successfully through the 1990s, or were they just too idiosyncratic?

Really, I mean, it’s sad, but it really doesn’t matter what SST achieved before that – if they sign Nirvana, then forget it, it’s over. SST is maybe still the biggest [indie label], it would change everything. But that didn’t happen.

I think you could go back even further when SST started having problems with Sonic Youth. If they [could have] fixed that, and I’m not really sure how – if it’s simply a matter of just paying them or if it was more complicated than that.

But the history of rock and roll is littered with stories of artists who started out as indie artists [and who] were just so royally screwed over that they went to the safety of major labels for protection, which sounds like you know, out of the frying pan into the fire, right.

You know, when Sonic Youth recorded ‘Daydream Nation’, which I think is probably one of the best albums rock albums of the 1980s, they were recording it for SST. But they become so disaffected [it came out on] Enigma, and then they went on to Geffen and when they when they went to Geffen, and they brought a bunch of people with them – former SST employees, former SST artists, Nirvana – it just changed everything.

I love the way the book ends with basically an open letter to Greg Ginn looking at a potential way forward. What would you like to see happen next with SST?

I really wrestled with that because I thought that I was gonna come across as naïve, but I love a lot of these bands and a lot of these records, too. And I would love to see that these records to get a second life, whether that’s with a revamped SST or the rights be reverted back to the artists. It would be great if some people could get to hear some of these bands again, you know, from Painted Willie, Das Damen and Screaming Trees. I mean, ‘Double Nickels on the Dime’ [you] can’t even get that record right now. So, it’d be really great if a lot of that stuff was made available.

I didn’t want to end on a really pointed note. I wanted it to be like, a ‘wouldn’t it be great if…’ kind of moment. If that made me look a little naïve and a little foolish, so be it. But I didn’t want my book to be the thing that shut the door and hardened anyone’s attitude towards this stuff. I would love to see these artists be able to have a relationship with Greg again.

‘Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise and Fall of SST’ is out now. Jim Ruland’s punk-adjacent, healthcare dystopia novel ‘Make It Stop’ is due in April 2023 from Rare Bird Books, and he’s working on ‘Rumors of My Demise’, a memoir from Evan Dando of The Lemonheads.

Follow Jim Ruland for more…

More of the latest in punk

- Rob Moss and Skin-Tight Skin release new album

- Latin Bands Honour Green Day’s Sophomore Album 30 Years On

- Ruts DC announce highly anticipated new album

- Skate punks Cigar return to visit

- Monkey Mind release new video ‘Black Clouds’

- PARKER Return With Anthemic New Single ‘Problems’

- Floggy Molly Partner With Ukrainian Filmmakers For ‘A Song Of Liberty’ Video

- HOODOO GURU’S Dave Faulkner and Brad Shepherd: My Punk Top Ten

- Interview: Pennywise Guitarist Fletcher Dragge

- The kids are alright as punk rocks The Horn at the Half Moon

- What Have Marty Love, Paul Gray, Baz Warne and Leigh Heggarty Got in Common? They’re all Wingmen

- Meryl Streek Slams Politicians Over Housing Crisis On Vitriolic New Single’ Death To The Landlord’

- The Homeless Gospel Chir Back with New Album

- Latest Supergroup L.S. Dunes Launch Debut Track

- Killed By Cupid Drops New Single feat. Jack Cumes

Links

An occasional writer on punk rock.

Click on Dom’s photo for more of his articles

Did you know that we are 100% DIY? We run our own game. No one dictates to us, and no one drives what we can or cannot put on our pages – and this is how we plan to continue!

Did you know that we are 100% DIY? We run our own game. No one dictates to us, and no one drives what we can or cannot put on our pages – and this is how we plan to continue!