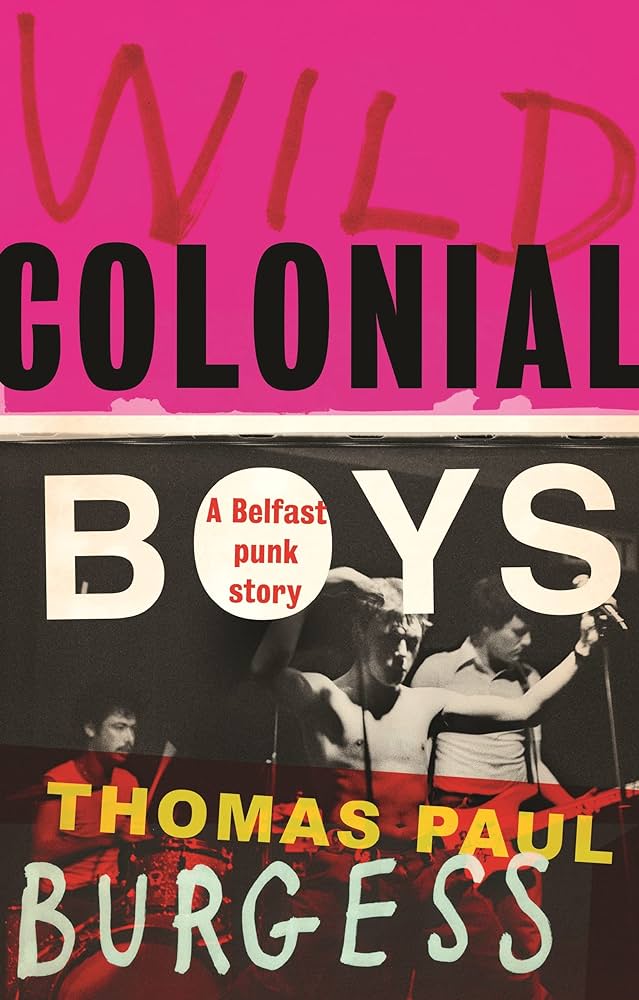

'Wild Colonial Boys' blends punk rock discovery with vital social history, told via the story of seminal Belfast punk band Ruefrex.

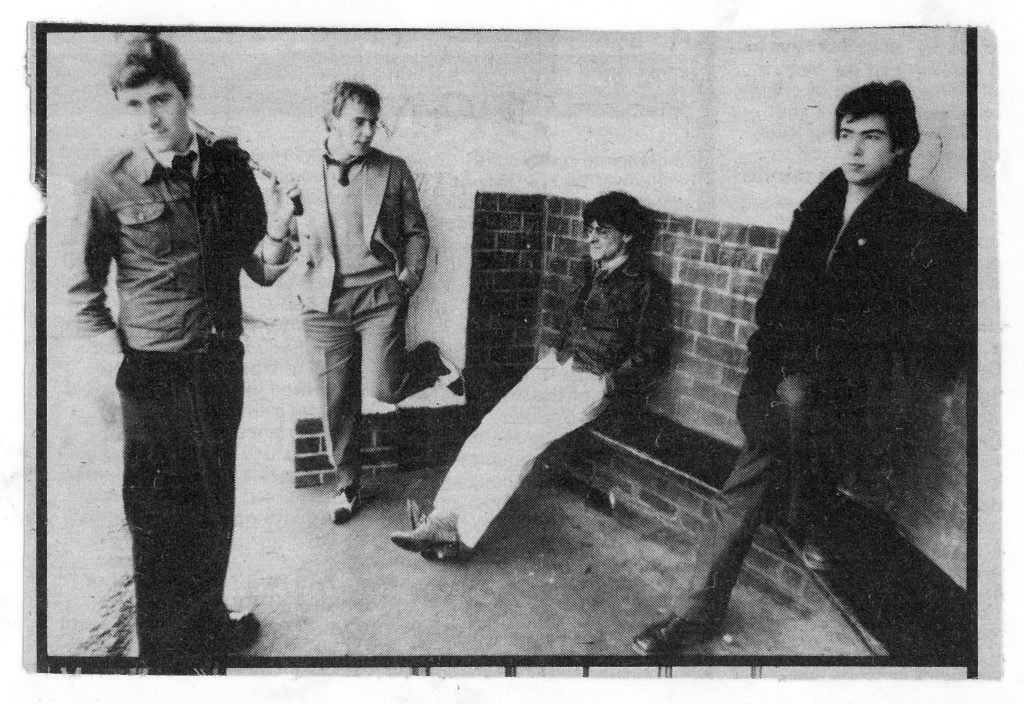

Ruefrex formed in Belfast in 1977, inspired and galvanised by the burgeoning punk scene that was boiling up and over the waters from England.

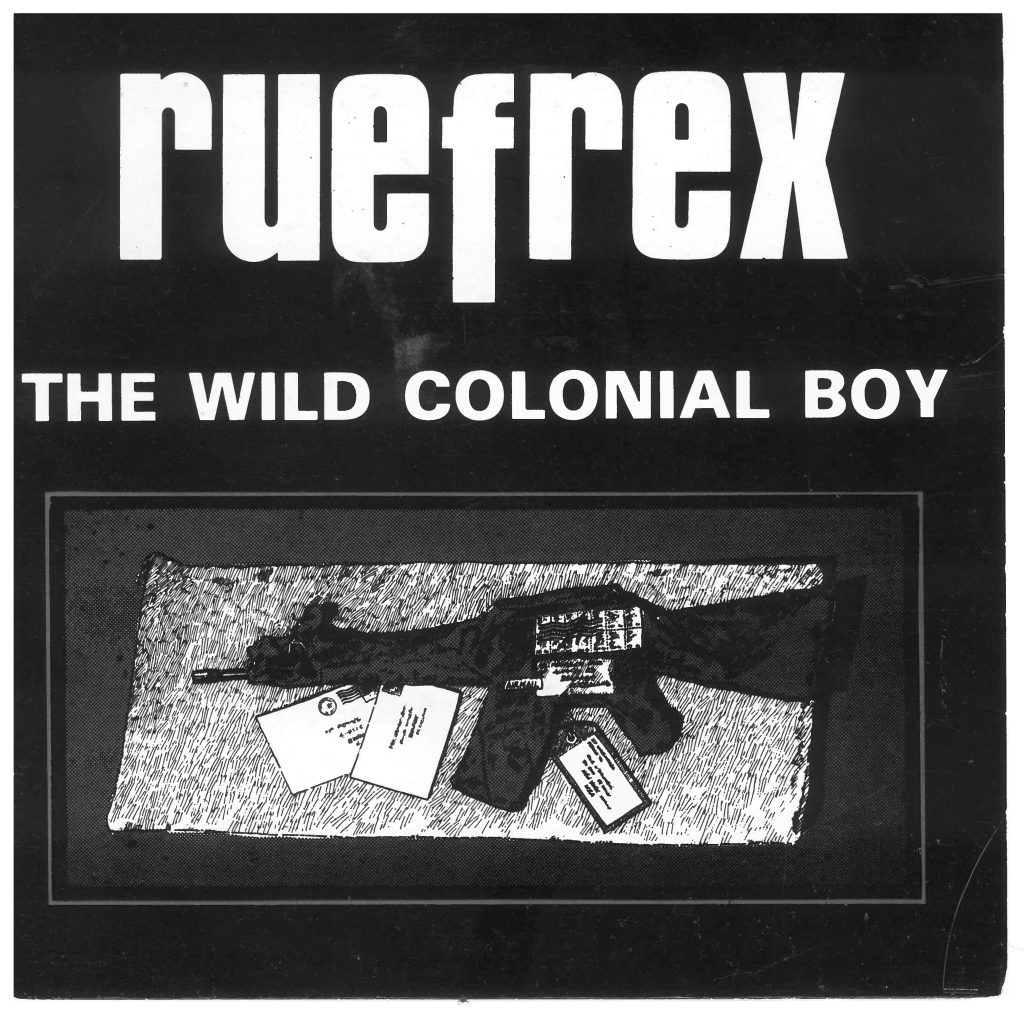

Originally called ‘Roofwrecks’ the band rebranded themselves early on, keeping the phonetic sound but adding a distinctly punk ‘X’ into the mix à la X Ray Spex, Generation X, XTC, Siouxsie Sioux (has there been a more punk letter? Maybe not until Musk ruined it). That rebrand may have come at such an early stage in the band’s life as to seem unimportant in the grand scheme, but it was done to give the band a more fitting name- a more serious, combative and intense name. A name that would convey a band not in it for the larks and the glory, but a band that have something serious to say in a time that needed people to be saying serious things. An aspiration and ethos that would come to define many aspects of the band’s career and the choices they made for better or worse (depending on how you look at it).

Burgess’ story does what all punk memoirs and biographies need to do- set out the political and social context that both nurtures and hinders but always defines the punk scene that springs out of it. And in Burgess’ case it is the complex and bloody history of the ‘Troubles’ in Northern Ireland that forms the backdrop- a part of the UK fighting a war over decades that has defined many parts of our modern history.

As punk in the late 1970s found its way onto Northern Irish shores, it brought with it a tumultuous medium to express political thoughts, grievances, ideas and utilise the oft revered ability punk has for subverting the official political messages of the state and instead, broadcasting directly from the communities, families and youths that need a voice and very rarely have one.

‘Wild Colonial Boys’ strikes a perfect balance of Burgess’ own story and inner most thoughts and perspectives, with the wider political context of the time. Burgess covers many themes like friendship, teenage idealism, socio-economic brutalisation and normalisation of violence that are given an even more poignant tinge when considering that not everyone described in the book- childhood friend, foe or acquaintance- made it out alive.

A consistent theme of the book is that age old conflict between wanting to use your platform to espouse and embody certain ideals and values, with the compromises needed to achieve fame and fortune. A compromise that Burgess was at times tempted to make but ultimately successfully resisted- sometimes causing friction with other groups (such as Stiff Little Fingers), movers and shakers like Good Vibrations’ Terri Hooley and most damagingly- fellow Ruefrex band members Tom ‘TC’ Coulter (bass), Jackie Forgie (guitar) and Alan Clarke ‘Clarkey’ as the frontman.

But in a situation so divided as the one in Northern Ireland at this time, every word, every action or endorsement can be scrutinised and amplified, playing into the tendency that the music press had at the time to simplify the Northern Irish punk counterparts as divided along binary sectarian lines- Catholic/Protestant, Republican/Loyalist. And for a band like Ruefrex, supporting an anti -sectarian message was one that not everybody was willing or able to absorb or comprehend.

But it clearly did win them some fans as hard graft and uncompromising ideals led them to pick up steady acclaim and devotion, tracks like ‘Wild Colonial Boys‘ and ‘Capital Letters’ placing in the UK charts as well as their frenetic and authentic live shows being a draw. They could count U2’S Bono as a fan and they were asked to accompany folk punk royalty The Pogues on tour which could have been make or break for the band (they were pulled from that tour with Burgess seeming to imply that an ill-fated remark during an interview calling the Pogues ‘professional Irishmen’ may have been the cause).

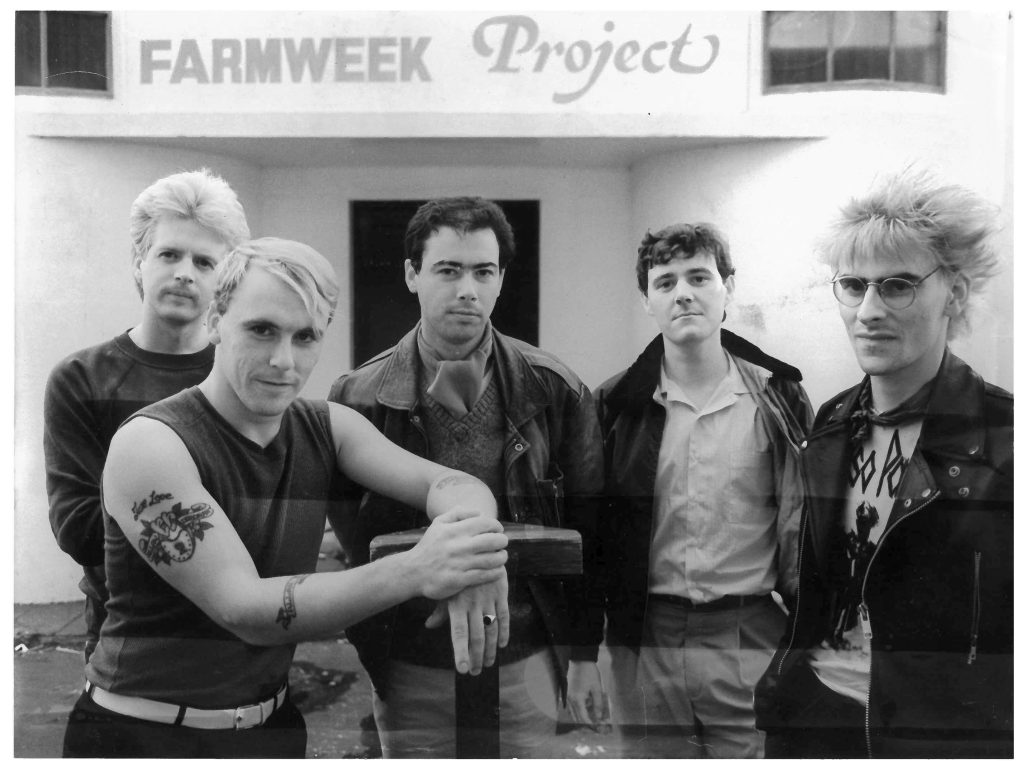

Burgess moved to London- a relocation that proved fruitful in some ways and the end of the dream in others. As is probably still the way now, London was a bit of a brain drain of musicians, many being lured to the capital with the idea that more connections and opportunities may present themselves. Instead, it becomes a business maze to navigate through as Burgess discovered when signing with legendary Stiff Records and getting the opportunity to record a full length album (‘Flowers For All Occasions’ 1985) which seemed to be the last hurrah for the band who by now were dispersed between England and Northern Ireland and undergoing frequent lineup changes (Garry Ferris and Gordy Blair played guitar and bass respectively on this LP as TC opted out).

Throughout this eventful and insightful story, the human cost of such divisive politics and embedded identities is demonstrated through some very touching and human encounters, that far from being a footnote to the story, are more revelatory than reading a political history of the Orange Order or the IRA. Two stood out for me. One being the moment Burgess presented his mother with the lyrics to an anti war song he had written (‘Poppies‘) but far from being enamoured by the articulate and astute words, Mrs Burgess was reminded of family members who had died in conflict, an anti war song seemingly undermining the pride and loss felt by (mainly working class) families who were personally touched by war.

The other was the story playing out in the background of Burgess’ London house share with a rather reclusive female resident whose emerging pregnancy became an unspoken spectre of the divide between two parts of the UK- this individual woman just one of many Irish girls who fled to England looking for an escape, a solution, anonymity or services that would not be an option in their own home.

There’s enough mythbusting in the book to ground it in a sense of real authenticity- Burgess challenges the orthodoxy that punk brought warring communities together universally, and that Terri Hooley’s Good Vibrations records was the only focal point of the scene. Even if punk could bridge some political gaps, others soon emerged which were probably not unconnected: “But other fissures form just like any scene- collectives and allegiances had already formed in the punk scene and schisms were starting to appear”.

The idea that Hooley was instrumental in creating a socialist utopia in his record shop is challenged by Burgess as being “by accident rather than by design” and perhaps a reminder to us all to be wary of mythologising individuals in a movement that has more than its fair share of rebels and visionaries.

The book ends full circle with Burgess leaving London behind and returning to his home of Belfast looking for the next chapter.

‘Wild Colonial Boys’ is a human and genuine look at one of the most important punk scenes- a scene that managed to perform two seemingly contradictory roles for those who were part of it simultaneously providing a distraction and everyday escape from the violent turmoil around them whilst also being their main outlet to express opinions about it. It was always there, not just in big political actions and incidents, but in small interactions and human relationships. And that’s punk- making sense of the world around you; engaging with the people around you. In Burgess’ words, punk is “a cause no one has to die for”.

‘Wild Colonial Boys: A Belfast Punk Story‘ is released via Manchester University Press on 30th January 2024. Get your copy HERE.

Follow Thomas Paul Burgess on Their Socials

Need more Punk In Your Life?

Griff and Michele are back with a Ska classic!

Follow-up single to their December hit ‘Christmas Smile’, Griff & Michele with one ‘L’ return with a cover of the 1968 Ska/Rocksteady/Reggae classic ‘54-46’, by

Crymwav to hit London on Friday!

West coast US rockers Crymwav (pronounced ‘Crimewave’) are crossing the pond to play a show at the famous Iron Maiden pub the Cart & Horses

Scarborough Punk Souvenir – are YOU in this fantastic photobook, by Phil Thorns?

Scarborough Punk Festival 2024 was an amazing event – top photographer Phil Thorns presents the best of the action! Published in a fabulous 72 page

Syama de Jong, ‘first lady’ of Dutch punk, passes away

Rest in Punk, Rest in Power, Saskia aka Sacha aka Syama de Jong! We shall never forget you. Herman de Tollenaere recounts her extraordinary legacy.

Peesh goes ‘Under the Radar’ in his new seasonal project!

Northumbrian punk singer-songwriter Peesh has just released a great new single, ‘Under the Radar’, to celebrate the first day of Spring – and to launch

Album review: Satanic Rites of The Wildhearts

March 2025 sees The Wildhearts return with their 11th studio album; ‘Satanic Rites of The Wildhearts’. Featuring their new line-up, coming out on a new

I’m Molly Tie- I Love punk! I play drums (badly), write a lot about punk (not as badly) and I’m particularly interested in issues relating to women in the music scene.

Did you know that we are 100% DIY? We run our own game. No one dictates to us, and no one drives what we can or cannot put on our pages – and this is how we plan to continue!

Did you know that we are 100% DIY? We run our own game. No one dictates to us, and no one drives what we can or cannot put on our pages – and this is how we plan to continue!