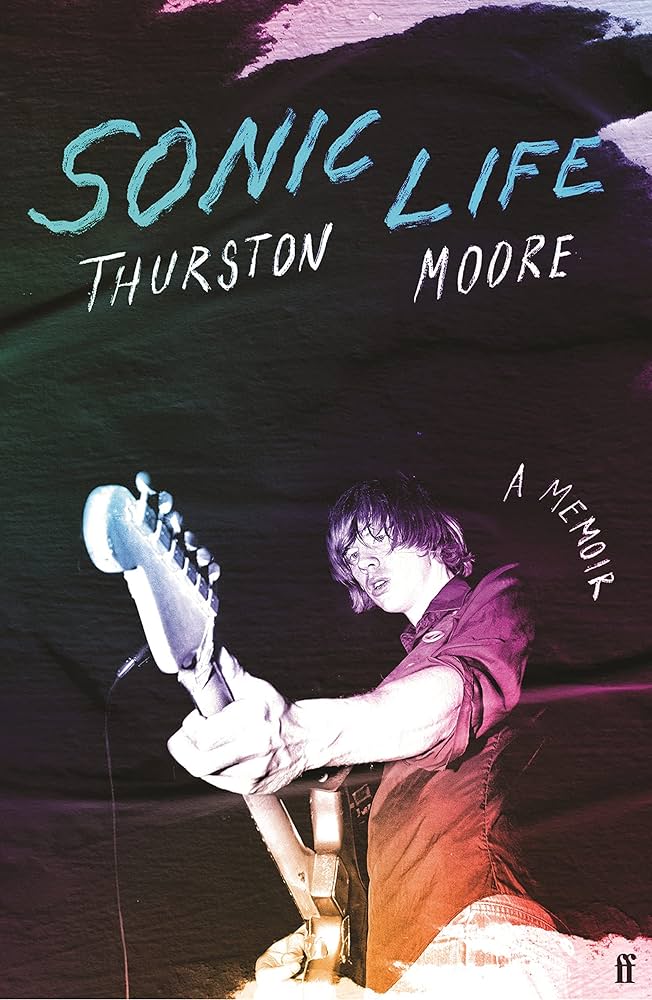

Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore reflects on the art and experiences that made him in his new memoir 'Sonic Life'.

Like fellow New Yorkers Velvet Underground before them, Sonic Youth straddled the great divide between the avant garde and the popular. Drawing on various ‘extreme’ forms of music (punk, no wave, free jazz, improv, modern classical), for three decades they used alternative tunings, dissonance, feedback and volume in crafting songs that set satnav for the expressway to your skull.

Perhaps the greatest merit of Thurston Moore’s book ‘Sonic Life’ is the way it puts the genesis and evolution of his band in context. Artists and art forms don’t simply emerge in a vacuum, and Sonic Youth are certainly no exception. On the contrary, they were very much a product of their circumstances: the melting-pot ‘post-apocalyptic playground’ that was New York in the late 1970s and early 1980s – dirty and dangerous, but a mecca for musicians and artists drawn by the prospect of cheap rents and plentiful opportunities, a city crackling with creative energy and experimental zeal.

When, after several false starts, the stars finally aligned and Sonic Youth formed around the axis of Moore, Kim Gordon and Lee Ranaldo, they put both the art and the rock into art rock, equally at home performing in galleries and loft spaces as playing in conventional music venues like CBGBs.

From the very start, Moore and his bandmates were attuned to those who came into their orbit and had the happy knack of knowing or getting to know the right people, establishing and nurturing creative relationships that would endure. If that was important when finding their feet in New York, it would prove invaluable once they started venturing beyond the city limits.

Like Michael Azerrad in his superb tome ‘Our Band Could Be Your Life’, and Bob Mould in a recent interview with Louder , Moore underlines how touring the US in the pre-internet days meant a reliance on emerging networks of bands, promoters, venues and fans, and on the enthusiasm and generosity of others.

While exploring their own country and forging friendships with the like-minded likes of Black Flag and the SST family in California was exciting, getting their first glimpses of Europe was something else. Sonic Youth smartly capitalised on connections made through Glenn Branca and immediately found an alternative ecosystem and audiences far more appreciative of their art than back home. Transatlantic trips soon became the norm.

Beginning life on the fringes of no wave, Sonic Youth gradually became a less forbidding art-rock outfit with each new release (and the addition of long-term drummer Steve Shelley), from 1985’s great leap forwards ‘Bad Moon Rising’ to 1988’s imperious double LP ‘Daydream Nation’.

But Moore remained a punk at heart – the kid who had fallen for the Stooges, the Ramones, Television and Patti Smith in his bedroom; the wide-eyed youth whose mind had been blown by live performances by Suicide and Sid Vicious. When hardcore first emerged, it found a fan in Moore, despite its blunt-force break-neck blitz appearing to have precious little in common with Sonic Youth’s often drawn-out abstraction.

From punk, Moore took the intensity and the determination to retain creative control. Sonic Youth may have signed to DGC and flirted with the mainstream in the early 1990s, but they continued to do everything on their own terms, becoming role models for others of how to retain underground credibility on a major label.

What’s more, they used their clout and stature to good effect, for the benefit of others as well as themselves – most famously, of course, with Nirvana.

As ‘Sonic Life’ perpetually illustrates, Moore has an insatiable appetite for music and culture more widely, and Sonic Youth took every opportunity to champion what they loved. This was met with unwarranted cynicism by a few, who saw the ‘Godfathers of Grunge’ as self-appointed alt-rock gatekeepers and arbiters of cool – something that clearly still stings.

The book arguably becomes less gripping when it moves into the mid-1990s, by which point Sonic Youth had settled into a familiar pattern of record, release and tour, having found creative freedom rather than disappointment in abandoning briefly harboured aspirations of significant overground success.

Moore recounts becoming friendly with teenage heroes Patti Smith, Ron Asheton and Tom Verlaine and getting to perform with David Bowie and Paul McCartney (so much for killing your idols). Some might see him as an incorrigible namedropper, but then many of those with whom he recalls rubbing shoulders (Nick Cave, Beastie Boys, Rick Rubin, REM, Jean Michel Basquiat) were relative unknowns at the time.

The narrative of a band by now entirely comfortable in their own skin and beloved for it is punctured on occasion – by a self-flagellating account of a disastrous performance at one of Neil Young’s benefit concerts, for instance, and by Moore’s recollection of a misguidedly experimental headline set at the Mogwai-curated All Tomorrow’s Parties festival in 2000. (For what it’s worth, I was there – in the photo pit – and lapped it up, but the show did prove that these supposedly sacred cows weren’t above criticism and still retained the capacity to confound and confuse even their core fanbase.)

If fault is to be found with ‘Sonic Life’, it’s in the way Moore fudges the band’s demise. His intimation that Sonic Youth had reached the end of their natural lifespan doesn’t chime with the fact that their final record, 2009’s ‘The Eternal’, was their finest since 1995’s ‘Washing Machine’, the sound of a band reinvigorated by the addition of Pavement’s Mark Ibold on bass and with plenty more to give.

It comes across as an attempt (conscious or otherwise) to explain away a split that was actually precipitated by his own infidelity and the breakdown of his marriage to Gordon – something that he touches on, but only briefly and reluctantly (unlike Gordon, who foregrounds it in her own book ‘Girl In A Band’). ‘Sonic Life’ may be subtitled A Memoir, but this is no intensely personal, warts ‘n’ all account like (for instance) Viv Albertine’s ‘Clothes Music Boys’.

Moore has insisted that he didn’t want to air dirty laundry in public for the sake of the couple’s daughter Coco, and he is of course entitled to remain tight lipped rather than obliged to be candid – but to imply that Sonic Youth’s time was up anyway is at very least questionable.

Moore is far more comfortable writing about music – about bands, gigs, encounters all around the world. Some may be sceptical at the level of detail and his extraordinary powers of recall, but no doubt memories were revivified by archive footage, photos and reports, and, unlike many of his contemporaries, Moore was never lost in the fog of drug addiction.

What ‘Sonic Life’ does particularly brilliantly is to convey his formative experiences pre-Sonic Youth, especially those that took place in cramped, sweaty venues. It transports you straight to the heart of the moment, into the moshpit, front and centre, amid the noise and chaos – offering vicarious thrills and standing as a testament to the remarkable power of live music.

‘Sonic Life: A Memoir‘ by Thurston Moore is out now.

Follow Thurston Moore on Socials

Need more Punk In Your Life?

Album review: Liliths Army release third album ‘Doll’

From Northampton, UK, Liliths Army are a trio band best known for touring, including in the US. Their music is a mix of lo-fi punk,

Supersuckers, London New Cross Inn, 10th April 2025

Yes, for the umpteenth time, the Supersuckers are still going! Cynics might say that’s because the veteran Seattle rock n’ roll trio have no plan

The Chords UK, helmed by Chris Pope, release the mammoth 44-track ‘But Then Again: The Best of The Chords UK’

Designed to truly tell the tale of The Chords UK, ‘But Then Again’ is an ambitious and inventive collection, featuring new and previously unreleased tracks,

Ronker, London New Cross Inn, 8th April 2024

We’ve just passed the 31st anniversary of Kurt Cobain’s death, and it’s safe to say that the much-missed Nirvana frontman would approve heartily of tonight’s

Scarborough Punk Festival: Still Punk’s Best Kept Secret

A killer lineup, coastal views, historic setting and one stage of pure punk energy delivering another unforgettable weekend of music, mates, and mayhem – Scarborough

Aerial Salad announce new 5-track 12″ ‘Roi de l’herb’ EP for June release

Manchester punk power-trio Aerial Salad are following last years acclaimed ‘R.O.I.’ album with a brand new 12” EP ‘Roi de l’herb’ to be released June

Ben is an editor based in Cardiff. He is a regular contributor to publications such as Buzz and Wales Arts Review, writing on everything from music, books and film to photography and food.’

Did you know that we are 100% DIY? We run our own game. No one dictates to us, and no one drives what we can or cannot put on our pages – and this is how we plan to continue!

Did you know that we are 100% DIY? We run our own game. No one dictates to us, and no one drives what we can or cannot put on our pages – and this is how we plan to continue!